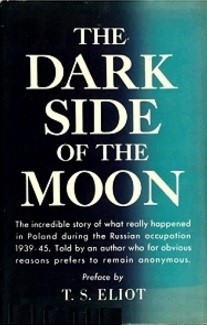

Dark Side of the Moon (Polish Deportations) - Zoe Zajdlerowa

Dark Side of the Moon

Zoe Zajdlerowa

1990

ISBN 0710813732

Hemel Hempstead, England: Harvester Wheatsheaf

98 Books about Poland | Polish War Graves in Britain

In 1940 the Soviet Union began the deportation of over one million Poles from their homes in Poland to penal camps and sites of exile in the far reaches of the Soviet Union. The Soviet Secret Police (NKVD) pounded on the doors' of Polish homes in the middle of the night, gave the occupants a short time to gather their belongings and then escorted them to waiting trains of cattle trucks which would take the Poles on their long journey into exile. Most of them would die in exile - never to see Poland again.

The Deportations

Mass deportations took place on four occasions.

- February 1940

- Whole villages of small farmers, forestry workers, former soldiers of the Polish-Soviet war in the 1920s who had been granted land, civil servants, members of the police.

- April 1940

- Families of men with the Polish Army, persons in trade, farm labourers from sequestered estates, small farmers.

- June 1940

- Refugees from other parts of Poland who were in Eastern Poland on 17 September 1939 when the Soviet Union invaded Poland.

- June 1941

- Any in the previous categories who had avoided deportation, children from orphanages, people in Polish prisons.

The February 1940 deportation took place in severe winter weather. A woman in the small village of Delatyn described her experience:

After midnight, whole convoys of sledges loaded with families who had been arrested went past the door all night. There were 33 degrees of frost...The neighbours stood outside their houses and prayed. The parish priest stood on a knoll by the church, holding out a great Cross towards those who were taken past...The trains, after being loaded, often stood for days before leaving...There were people who went out of their minds from horror and shock. (pp. 63-64)

The Train Journey

As the trains left on their long journey Poles threw scraps of paper out of the trucks with their names and addresses on them hoping that someone would find them and pass on a message.

The author, Zoe Zajdlerowa, records that the Poles would often release their emotion in song.

More than once, as a train moved...a few voices first, and then a choir, and then thousands of aching, parched throats, bursting with sorrow, would raise the notes of some pealing Polish song of faith and praise...They are the songs of the Old Republic, the songs of the Polish Golden Age, the songs of the Partitions. (pp. 65-66)

The songs uttered always the same thing:

- Ineradicable love of Poland

- Proud faith in God

- A passionate determination to be free or die

The conditions on the trains were appalling. Food and water was in limited supply.

Bread (sour and black and badly baked) was handed out on most trains at intervals of two or three days...Occasionally a few buckets of fish soup with fish heads and bones were distributed, but this was very rare...The water situation was absolutely drastic...In late spring and summer when passing through the scorching lands of the Ukraine and the central deserts, a pitch of suffering was reached which can never be estimated or described...Tongues turned black and stiff and protruded from ghastly mouths and throats. (pp. 69-70)

The horrors of the long train journeys were many:

- Lack of privacy

- Thirst and hunger

- Fatigue

- Epidemics

- Vomiting and diarrhoea

- Dysentery and bleeding

- Nostalgia

- Roughness of the soldiers

At the end of the train journey the Poles would have a further journey by truck or foot to reach their ultimate destination somewhere in Siberia or Kazakhstan.

Life in Exile

One of the Polish exiles describes what happened after their 15 day train journey came to an end at a place called Ayagouz, a day's journey from Alma-Ata in Kazakhstan.

We were ordered to climb onto high lorries...Many could scarcely crawl...everything was unspeakably desolate...at last a settlement was reached...about 200 persons were unloaded here and were told nothing...no quarters of any kind had been provided. The natives, who were abominably overcrowded themselves, were expected to house us in corners of their huts...everywhere was alive with bugs and vermin. (p. 138)

Most of the families deported consisted of women, children and the elderly. The women struggled to keep their children alive and to keep them Polish. The women had to fight:

- Cold

- Hunger

- Heat

- Disease

- Terror

- Exhaustion

- Sovietization

They fought to care for their children's minds and souls. In Soviet schools the Polish mothers knew that Soviet influence could mark their children for life.

The mothers...knew by experience the teaching, the attitude towards religion and the ethical standards enforced in them...Polish mothers throughout the whole of Polish history...believe...there are worse things than physical hunger, ill-treatment and solitude...these worse things, from perversion of the mind and abdication of the spirit, and not from the pain and fears of the body, a Polish mother strives to safeguard her child. (p. 151)

Poles Released

On 22 June 1941 Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union. The Soviet government signed a pact with the Polish government-in-exile in London on 30 July 1941. This pact contained the following:

The government of the USSR declares its assent to the raising on the territory of the USSR of a Polish Army...The government of the USSR will grant an amnesty to all Polish citizens at present deprived of their liberty within the territory of the USSR. (p. 153)

The Polish Ambassador to the USSR and his small staff had the enormous task of organizing relief for Poles in the Soviet Union. Their first task was to find the Poles. They setup orphanages, feeding centres, hospitals and schools throughout the USSR. Poles who had been released from penal camps and exile made their way by whatever means possible to where the Polish Army was being reformed.

Hundreds of thousands of persons travelled by rail, by water, in carts, on foot...All were undernourished, physically and mentally exhausted. All were...obsessed...with getting to their own people...Enormous numbers were children and for the most part orphans. (p. 158)

The Polish Army in the Soviet Union and some civilians were evacuated from the Soviet Union in 1942. Many Poles were left behind and were never able to escape from the Soviet Union.

Zoe Zajdlerowa was the daughter of a Protestant minister in Ireland. She married a Pole, Aleksander Zajdler, in the 1930s and lived with him in Poland. She escaped from Soviet occupied Poland and arrived in England in 1940. She was separated from her husband during the escape and never saw him again.

- Crater's Edge: A Polish Family's Epic Journey Through Wartime Russia - Michal Giedroyc

- The Silver Madonna - Eugenia Wasilewska (Polish Deportation to Kazakhstan)

- Janek Leja - A Polish Survivor of Siberian Labour Camps

- Paying Guest in Siberia - Maria Hadow (Polish Deportations to Kazakhstan 1940)

- No Place to Call Home - A Polish Survivor of the Soviet Gulag (Kolyma, Siberia) - S Kowalski

- Polish Deportations to Kazakhstan 1940 (Unsettled Account - Eugenia Huntingdon)

- Polish Deportations to Kazakhstan 1939-41 - Wesley Adamczyk (Siberia)

- Shallow Graves in Siberia - Michael Krupa (Polish Deportations)

- A Forgotten Odyssey - The Untold Story of 1,700,000 Poles Deported to Siberia in 1940

- The Ice Road - Stefan Waydenfeld (Polish Deportations, Siberia)