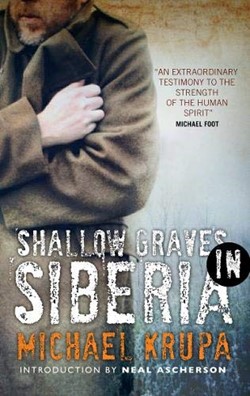

Shallow Graves in Siberia - Michael Krupa

Shallow Graves in Siberia

Michael Krupa

2004

ISBN 1843410125

Edinburgh, Scotland: Birlinn

98 Books about Poland | Polish War Graves in Britain

An extraordinary tale of survival and escape from Stalin's concentration camps in Siberia. Michael Krupa, a Pole, was captured by Soviet forces in eastern occupied Poland shortly after the outbreak of the second world war. He was accused of being a German spy and sent to the NKVD Lubianka prison in Moscow. There he was interrogated and beaten.

The Soviets found him guilty of spying and sentenced him to 10 years hard labour in a concentration camp in Siberia. He was then sent by train, travelling in a cattle truck, to a camp called Pechora. The final 280 miles of the journey was completed on foot in harsh winter conditions. Many died on the march to Pechora. His dream was to escape from the Pechora camp and return to freedom.

Captured by the Red Army

Michael Krupa was born and grew up in a small Polish village called Rudnik near the ancient Polish capital of Krakow. His father was the manager of a small agricultural shop in the village. For Poles religion was of great importance and his parents encouraged him to enter the priesthood as having a priest in the family was a great honour. He studied for four years at the Jesuit Seminary in Nowy Sacz and then entered the Jesuit Order by joining the monastery at Stara Wies in the south of Poland.

He later decided that he could not accept life in a monastery and planned his escape from it. Early one morning he scaled the monastery walls and set out to travel to a town called Stolpce, near the Polish-Russian border on the River Nemen, where his uncle lived. After later returning to Krakow he was called up for compulsory army service. He was overjoyed to join the 13th Regiment of Cavalry in Nowa Vilejka in the north of Poland. When the Germans invaded Poland on 1st September 1939 his cavalry regiment was sent to the front line.

...we managed to destroy eight German tanks before our ammunition ran out. The German panzers then pushed us back towards the Vistula...Though we fought like lions, there was no escape...but to swim the river with our horses...The Vistula was full of the bloodied bodies of men and women...We then learned that we were almost entirely surrounded and that the Soviet army had advanced into the eastern provinces of our country...Some Polish regiments had successfully crossed the Hungarian frontier...It quickly became every man for himself in this game of survival. Our regiment ceased to exist. (pp. 23-24)

Michael Krupa then made his way to his home village of Rudnik. There he discovered that his family had gone to stay with relatives in the East. Due to his excellent command of the German language he was able to apply for a Bescheinigung Karte which was given to Poles who could speak German and which would enable him to travel freely in German occupied Poland. He headed for Przemysl, a town whose river was the dividing line between German and Soviet occupying forces in Poland. He managed to cross the river but was captured by Soviet forces.

Pechora Labour Camp

Life in the Pechora concentration camp was hard. Inmates had to fell trees, trim them and cut them into the right lengths. If a prisoner achieved the daily norm he received the daily food ration of one loaf of bread, soup and vegetables, hot water and a cube of sugar. If he produced less than the norm he got less food.

Every's prisoner's dream was to break free from the misery and degradation of the penal camps. But the chances of escape were remote. Hundreds of miles of forests, hungry packs of wolves, the bitter cold, knee-deep snow and army patrols stood between a would-be-escaper and freedom...I hated Siberia and slavery. I had been born free in the mountains of Poland. The only reason I survived in these wild, desolate forests was my iron will and my determination to become a free man again. (p. 80)

In June 1941 Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union. Conditions in the camp became worse due to food shortages. Inmates who were familiar with the maintenance of telephone lines were then given the opportunity to work outside the camp. Michael Krupa who had been in Signals in the Polish Army was offered the chance to be a telephone line repairman. He accepted and was taken to the main telephone center in Troitsko Pechorsk where he was given a horse so that he could repair telephone lines between the small siberian settlements. For three months he planned how to escape. In front of him lay a journey of 4000 miles to Afghanistan, many adventures and a return at last to freedom.

Michael Krupa died on 6th October 2013 aged 98.

- Dark Side of the Moon (Polish Deportations) - Zoe Zajdlerowa

- Crater's Edge: A Polish Family's Epic Journey Through Wartime Russia - Michal Giedroyc

- The Silver Madonna - Eugenia Wasilewska (Polish Deportation to Kazakhstan)

- Janek Leja - A Polish Survivor of Siberian Labour Camps

- Paying Guest in Siberia - Maria Hadow (Polish Deportations to Kazakhstan 1940)

- No Place to Call Home - A Polish Survivor of the Soviet Gulag (Kolyma, Siberia) - S Kowalski

- Polish Deportations to Kazakhstan 1940 (Unsettled Account - Eugenia Huntingdon)

- Polish Deportations to Kazakhstan 1939-41 - Wesley Adamczyk (Siberia)

- A Forgotten Odyssey - The Untold Story of 1,700,000 Poles Deported to Siberia in 1940

- The Ice Road - Stefan Waydenfeld (Polish Deportations, Siberia)