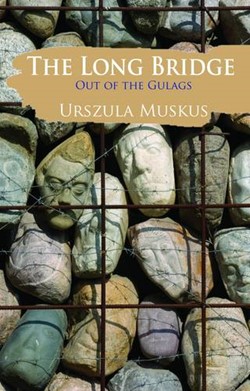

The Long Bridge - A Polish Prisoner of Stalinist Russia

The Long Bridge - Out of the Gulags

Urszula Muskus

2010

ISBN 9781905207558

Dingwall, Scotland: Sandstone Press

98 Books about Poland | Polish War Graves in Britain

In Rawa-Ruska, a town in eastern Poland, the summer of 1939 was coming to an end. The market square was filled with the fruits of autumn. The harvest the best since that fateful year of 1914. Once again, however, the peace and quiet of this Polish county town was about to be shattered.

Out of a clear blue sky Nazi Germany attacked and invaded Poland. Rawa-Ruska was bombed. The German army occupied the town, the Gestapo broke into houses and terrorised Jews. Under the terms of a secret agreement between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union the Soviets also invaded Poland. The Nazis and the Soviets divided Poland between them. Rawa-Ruska was to be in the Soviet zone of occupation.

Mass Arrests

The Soviet Secret Police (NKVD) began mass arrests of Polish citizens. Urszula Muskus, a 36 year old Polish woman, lived in Rawa-Ruska with her husband and family. Urszula's brothers were both arrested. On 6 January 1940 her husband was also arrested. A month later during a cold February night the NKVD arrested Urszula and her two children. They were taken to the railway station and put onto a train of cattle trucks. Along with many other Polish families they were being deported.

For hour after hour they waited in the train. Looking trough a tiny window Urszula saw her young parish priest Father Stokola.

He stood erect and, as he blessed us with the sign of the Cross, we could see the tears trickling down his face. (p. 20)

Eventually the train left and they headed east. They crossed the frontier between Poland and the Soviet Union and when they did so they sang the Polish National Anthem. The train travelled through the Ukraine and into Russia. They crossed the wide rivers of the Don and Volga. They came to the Ural mountains and headed south-east to Asia. Thirteen days after leaving home they arrived at Alga in Kazakhstan.

Torn away from the ancient civilisation of the West, we were now dumped here, in another world, upon the primitive, wild steppe of Kazakhstan. (p. 25)

Life in Kazakhstan

Urszula and her children were taken by lorry, on a journey of several hours, to a collective farm. They were told they were to work in the fields and that they would be paid in kind when the crops were harvested. They amassed 240 work days but Urszula realised that their wages would be insufficient to see them through the winter. She decided to walk, which took all day, to the town of Aktyubinsk and got approval from the NKVD to move her family there and to knit sweaters in order to try and make a living.

On 22 June 1941 Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union. The Soviet leader Stalin in an agreement with the Polish government-in-exile in London granted an amnesty to all Polish prisoners.

...groups of Poles released from Soviet prisons and concentration camps, began to arrive [in Aktyubinsk]. They were half starved, in rags and without means of existence. They needed immediate help. (p. 50)

Urszula demanded of the local authorities that they helped provide for these released prisoners. She secured a bread ration and some accommodation. A rumour circulated that a Polish Army was being formed in the Soviet Union. Urszula heard that a rallying point for released prisoners had been organised at Totskoye. She received permission to go there by train.

After three days I got off on Totskoye station where I could not believe my eyes! The station was full of Polish uniforms - although worn out, but on the faces of their wearers joy and enthusiasm were visible. (p. 51)

Urszula spoke to Polish officers and was told that the main headquarters of General Anders, commander of the Polish Forces in the Soviet Union, was at the next railway station Buzuluk. She went there and met with General Anders and briefed him on the conditions faced by those deported to Kazakhstan. Later she established contact with the Polish Embassy in Kuybyshev. She received official documents from them nominating her as a relief officer for Polish citizens in the Aktyubinsk area.

Arrested by the NKVD

On 10 May 1942 Urszula was arrested by the NKVD. She was told that she was being charged with espionage. Urszula left her young daughter in the care of an old granny.

Urszula was escorted by the NKVD on a train journey to Alma-Ata which was a number of days away. There she was put in prison and interrogated by the NKVD for a number of weeks. The sessions lasted between 16 and 20 hours at a time. They wanted her to sign a confession that she was guilty of espionage.

After a number of months Urszula and many other prisoners were taken by special train to Karabas.

Karabas was really like a large slave centre. Thousands of captives passed through it every day...The convicts...belonged to two distinct categories...quiet...terrified...these were the political prisoners. Others were sure of themselves...they were the worst habitual criminals in the Soviet Union. (pp. 86-89)

In December 1942 Urszula was taken on a two day march to an NKVD forced labour camp at Shakan. Winter in Kazakhstan is harsh with temperatures between -35 and -50 celsius.

...hard work and severe under-nourishment quickly undermined our strength and health and the death rate amongst the prisoners soared. (p. 103)

Urszula was moved to another camp at Berazniki in the spring of 1943. The commandant told her that she had been sentenced to 10 years in the NKVD camps. For the next few years Urszula was moved from camp to camp in the Karaganda area of Kazakhstan.

In the spring of 1952 Urszula's ten year sentence came to an end. She was told she was being released from prison but due to a special order she would spend the rest of her life in the Krasnoyarsk region of Siberia. She was put on board a passenger train travelling towards Vladivostock.

For the first time in ten years I was travelling in a passenger train looking out with interest through an unbarred window. On stations we were allowed to leave the carriage and talk to free people...On the third day the train halted at a small stop in the taiga...I was fully aware of the consequences of deportation to the taiga and yet as I left the train I felt happy and free. (pp. 274-275)

Freed from Capitivity

On 6 March 1953 Stalin died. Two months later came the news that Beria, the head of the NKVD, had been executed by the Soviet state. Urszula and the others living in the taiga experienced joy at this news but she noticed that the NKVD were frightened.

In December 1955 Urszula was freed from exile in Siberia. She travelled on a train from Krasnoyarsk back to Przemysl in Poland.

Returning home from permanent settlement in Siberia there were in the train about 800 Polish citizens travelling in Pullman coaches without a care for tomorrow...Every day I had white bread with butter, drank tea with sugar and ate food I had not seen for 16 years...There was singing in every railway carriage. People walked the length of the train looking for members of their family or friends. (p. 303)

The train arrived at Lwow and then the next afternoon it crossed the new Polish-Soviet frontier and soon after arrived in Przemysl. Urszula's sisters greeted her at the station and took her to their home.

Urszula made contact with her son and daughter now living in England. In 1957 she received permission to leave Poland for the UK. She arrived in London to be reunited with her son and daughter. Urszula died aged 69 in 1972 in the UK.

Related Material

- The Long Bridge - Urszula Muskus. Information about the author together with photographs on the website of her grandson Peter Muskus.

- The Long Bridge: Out of the Gulags: A Review, Irene Tomaszewski, The Cosmopolitan Review.

- Polish Deportees in the Soviet Union - Michael Hope

- Dark Side of the Moon (Polish Deportations) - Zoe Zajdlerowa

- Crater's Edge: A Polish Family's Epic Journey Through Wartime Russia - Michal Giedroyc

- The Silver Madonna - Eugenia Wasilewska (Polish Deportation to Kazakhstan)

- Paying Guest in Siberia - Maria Hadow (Polish Deportations to Kazakhstan 1940)

- Polish Deportations to Kazakhstan 1940 (Unsettled Account - Eugenia Huntingdon)

- A Forgotten Odyssey - The Untold Story of 1,700,000 Poles Deported to Siberia in 1940

- The Ice Road - Stefan Waydenfeld (Polish Deportations, Siberia)