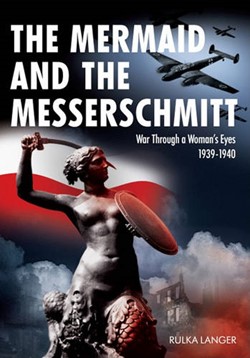

Mermaid and the Messerschmitt - Rulka Langer

Mermaid and the Messerschmitt

Rulka Langer

2009

ISBN 9781607720003

Los Angeles, CA: Aquila Polonica Publishing

98 Books about Poland | Polish War Graves in Britain

On 1st September 1939 Nazi Germany invaded Poland. That morning Rulka Langer was late for her job at the Bank of Poland. She arrived just in time to hear her head of department tell staff that German forces had crossed into Poland at almost every point. Poland was at war.

Rulka Langer lived with her mother and two small children in an apartment in Warsaw at Mokotowska 57. Her first thought was to get them out of the city. She borrowed a car from the American Embassy and had them taken to the home of her mother's childhood friend ten miles from Warsaw. Rulka returned to her apartment where she heard the noise of anti-aircraft guns and looked out to see German bombers flying in triangle formations overhead. The noise was deafening. The window panes shook. The city of Warsaw was under attack.

Early Life

Rulka was born in 1906. Her father was editor of the conservative daily newspaper Slowo (The Word). He died when she was only 18 months old. When Rulka finished school she entered the Warsaw School of Commerce. In her third year she was offered a scholarship to study in the United States. At 19 she left Poland to study for two years at Vassar College. On her return to Warsaw she took a job at the J Walter Thompson advertising agency. In 1930 she married her boss at the agency Olgierd Langer. Olgierd was offered a diplomatic job at the Polish Embassy in Washington. They went to the USA but later returned to Poland. In the spring of 1938 Olgierd left again for the USA to take up a position as trade commissioner. Rulka intended to join him later but Hitler's army arrived in Poland before she was able to leave.

The Siege of Warsaw

The Germans laid siege to Warsaw. Food supplies were short. People queued for hours. Everywhere Rulka Langer went she saw signs of destruction from the shelling of the German artillery. At 8.30pm each evening the Mayor of Warsaw, Stefan Starzynski, would broadcast to the city. His words gave Varsovians renewed strength and purpose.

...he reminded them every night, that destruction, hunger; even death no longer mattered. Something bigger was at stake. Poland's honor. Poland's fate...Warsaw was not a city any more, it was Poland itself. And in that hour of supreme test the proud Mermaid would not, could not fail. (p. 228)

During the early hours of Sunday 24 September the German guns pounded the city constantly. Rulka and her family, now back in Warsaw, went to church that morning. The church was packed. The congregation sang the hymn:

God Thou Holy - God Thou Mighty,

Mighty and Immortal,

Have mercy upon us!

It wasn't God that answered; it was the German artillery. Wheeeeeeeeew - Crash!

But still the hymn continued, stronger, more insistent,...

Deliver us, O Lord

...from sudden and unexpected death

Save us, O Lord!

But there was no mercy. The bombardment continued, furious, inexorable.

(p. 258)

That Sunday evening Rulka's mother called her to the window of their apartment. The Church of the Saviour was on fire.

It was burning like a torch with huge flames leaping high in the sky. The two gothic steeples, sharply outlined against the red and golden background of flames...It was a glorious and horrible sight. For a long time we watched it in silence. (p. 268)

Warsaw Surrenders

Warsaw was bombed relentlessly by the Germans on 25 and 26 September. The next day the city surrendered.

In the streets people wept. Others went around with stony faces. Through the devastated city the wind blew gusts of dust and ashes. The smell of smoke still hung in the air... (p. 310)

The reason given for the surrender of the city was the destruction of the water supply. The Germans did not immediately enter the city. They gave Varsovians a week to clear away the barricades, repair utilites and bury the dead.

In the weeks that followed Rulka slowly realised the extent of the German destruction of the city. The Royal Castle, government buildings, palaces, the Opera House, cafes and shops all destroyed.

Nothing but a huge cemetery of twisted, charred ruins, a ghost of a city. When for the first time I walked through Nowy Swiat and the Krakowskie Przedmiescie, I cried. (p. 310)

Rulka was shocked when she first saw the sight of German uniforms in the city.

There were more of them every day. Their trim gray-green uniforms struck a sharp contrast against the background of the ruined city and its shabby, haggard-looking inhabitants. (p.332)

Life in Warsaw

Rulka wanted to let her husband know that she and the children were safe. She learned that if you knew someone in the State Department in Washington the German military command headquarters might agree to transmit your message to them. Rulka visited the German HQ and they agreed to send her message.

On a bleak October morning Rulka's mother went to church. She was surprised to find that no mass was being celebrated at any of the altars. The church was dark as no candles were lit. She found out that at 7.30am that morning all the priests in Warsaw had been arrested. The Gestapo were responsible.

Christmas came and Rulka's young daughter was worried about the fate of the angel that brings Christmas presents to Polish children. She knew that the Germans shot anyone who was out after dark and was worried they would shoot the angel too. The family each broke thin white wafers, at the Christmas Eve meal, wishing each other luck. It was Rulka's mother who expressed what they all wished for: Poland to be Free.

Departure to America

The new year of 1940 brought bitter cold to Warsaw. For two months the temperature never rose above zero. Pneumonia was rife. One day Rulka returned to the apartment and her mother handed her a letter. It was from the US consulate in Warsaw. The letter told her that the consulate had instructions to issue her with a visa for America.

Rulka had known for months that her husband had been doing everything he could to secure her exit from Poland. The US consulate gave her and her children a visa, train tickets from Warsaw to Genoa in Italy, 10 dollars and notification of reserved passage on a liner to the USA. However, German red tape meant that there were many formalities and permissions to be obtained before they could leave.

On the day of Rulka's departure she said a tearful farewell to her mother who she was leaving behind. Her train left Warsaw for Cracow at midnight. She found herself in a dimly lit compartment surrounded by German uniforms. On arrival in Cracow they had to wait all day for the night train to Vienna. From Vienna they took a train to Italy. They had finally left the Reich and were free once again. Rulka never saw her mother again.

The publishers of The Mermaid and the Messerschmitt are Aquila Polonica. They are a company specialising in the publication of books, in English, about the Polish experience in World War Two. They have acquired the rights to publish over thirty books. The Mermaid and the Messerschmitt is their first book. Their second book was The Ice Road by Stefan Weydanfeld. Aquila Polonica was founded by Stefan Mucha and Terry Tegnazian.

- Aquila Polonica Finds Its Niche - an article on the Publishers Weekly website (3 May 2010).

- Polish Heroes by Terry Tegnazian in the Wall Street Journal (PDF) 1 June 2010

- A five minute video interview with Terry Tegnazian, talking about Rulka Langer and The Mermaid and the Messerschmitt, on Lifetime Television (USA) 25 May 2011