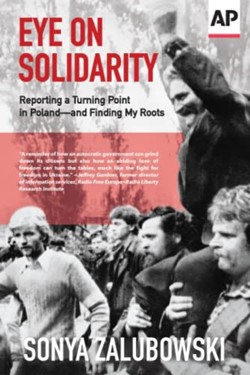

Eye on Solidarity - Sonya Zalubowski

Eye on Solidarity : Reporting a turning point in Poland - and finding my roots

Sonya Zalubowski

2023

ISBN 9780917360008

New York NY: Associated Press

98 Books about Poland | Polish War Graves in Britain

Sonya Zalubowski had a dream: she wanted to be a Foreign Correspondent and she wanted to discover her Polish roots. Working as a news editor in New York, with United Press International, she was growing tired of waiting for the opportunity to fulfil her dream.

In Poland, her ancestral home, she admired the courage Poles were showing in their struggles for greater freedom from Soviet control. The independent Polish trade union Solidarity, founded in 1980, was demanding economic and political reforms from the Polish government. Sonya Zalubowski decided that she wanted to tell the Polish people's story to the world so in early 1981 she took a leave of absence from United Press International and set off for Poland.

Arrival in Warsaw

The only Polish visa that Sonya Zalubowski could obtain was that of a student. She started a course learning the Polish language at Warsaw University. Her arrival on a foggy afternoon introduced her to the gray dullness of a Polish winter. A tiny shared room in a student dormitory on Zamenhofa Street was where she had been assigned living quarters. The food in the dormitory was dire. The toilets were even worse. She feared arrest by the Secret Police if the Polish government found out what she intended to do. Perhaps I should just go home she thought.

Life in Poland was grim:

- Widespread shortages

- Sporadic labour strikes

- Fear of Soviet invasion

Sonya thought: "Give it a chance, one day at a time".

A private rental notice on a housing bulletin board offered a way out of the student dormitory:

The next day I found Pani Alina. Her monthly rent for my room [in her apartment in Flory Street near Lazienki Park] took my enitre stipend. But in housing-short Warsaw, expensive as it was, it was a find, especially just for zlotys, no dollars. (p. 21)

Sonya needed more money to survive in Poland. She needed to exchange US dollars for Polish zlotys. There was the official exchange rate but the black market rate was four times better than that. Poles were not supposed to keep US dollars and exchanging currency on the streets could lead to arrest. Sonya took the risk, found a taxi driver who needed dollars to buy a new car in Berlin, and made the exchange. She could now afford to eat at an Old Town restaurant.

Solidarity

Every morning at 8 a.m. Sonya listened to the VOA or BBC news on her short-wave radio. There was a report one morning about the trade union Solidarity. Polish police had beaten and injured dozens of workers at a Solidarity sit-in at the prefecture in the town of Bydgoszcz, north-west of Warsaw. The Solidarity leadership reacted by demanding that those responsible for this be removed or they would call a general strike. The UPI bureau chief in Warsaw called Sonya and asked if she could come immediately to their office. They wanted to know if Sonya could help in covering this story. Sonya instantly said yes.

Negotiations between the Polish government and Solidarity came to an impasse. Solidarity declared that there would be a four-hour national warning strike on 27 March 1981. If Solidarity's demands were not met then there would be a general strike four days later on 31 March. Sonya had a friend who arranged for her to report on the strike from within the main cement plant in northern Warsaw.

I woke at 6 a.m. the day of the warning strike ... and made my way to the cement plant where my friend said her uncle [Stefan] would meet me ... At the plant a man with a red-and-white Solidarity armband let me in. "I am Stefan", he said. "We have been waiting for you. We want the world to know our story." (p. 42)

Polish flags flew everywhere in the factory and a large Solidarity banner saying strajk (strike) hung on a back wall. Both men and managers wore Solidarity armbands. At 8 a.m. the sound of the factory whistle signalled the start of the four-hour strike. One of the workers Sonya interviewed said:

"We must stand up to them now. We have a chance with Solidarity for a better life." (p. 44)

The strike ended at noon and the men went back to work. Sonya filed her story at the UPI bureau in Warsaw and it appeared on the front page of The Washington Post. The next day Solidarity said its demands had not been met by the Polish government therefore the general strike on 31 March would go ahead. Polish TV showed images of Warsaw Pact troops moving around Poland. Anxiety in the country was rising. However, on the eve of the strike it was called off. The Polish government said it would review Solidarity's demands.

Shortages

Supply shortages in Poland were acute. Poles spent many hours queueing for basic food supplies. The Polish government had imposed rationing. Pani Alina had said to Sonya: "Sometimes I get so hungry, but what can I eat?"

The government wanted to end the hoarding that had led to severe meat shortages, long lines and discontent ... Since I [Sonya] had arrived in Poland, the lines caused by shortages had grown to include milk, eggs, butter, cheese and vegetables. (pp. 48-49)

Food was available from private markets but at a price six or seven times that set by the Polish state. Private sellers could be seen at wooden stands outside state food shops:

Old woman in head scarves and peasant dress stood in their aprons in front of tables piled with apples, spring lettuce and chives grown in hothouses, huge white mushrooms and potatoes and carrots still muddy from the ground ... The prices were high. (p. 54)

Polish Pope John Paul II

On 13 May 1981 the Polish Pope John Paul II was shot in St Peters Square in the Vatican in Rome. Sonya and Pani Alina sat on the settee and watched the terrible news on Pani Allina's small television.

"He is being operated now," Pani Allina said, translating the reports. "Four bullet wounds, two to the stomach area." Starting to cry, she turned to me, "You think Russia behind this?" (p. 92)

Sonya decided she needed to find out how the Polish people were reacting to the news. She headed to St. Ann's church where an outdoor mass was to be held. Thousands of Poles filled the streets as she approached the church.

Priests, nuns, children and working people held lit candles and carnations in the red-and-white colours of the Polish flag. Many faces were wet with tears. ... An old woman cried next to me, "God help us", she said, "What will happen to Poland next?" (p. 93)

A taped message over loudspeakers, from the critically ill Cardinal Wyszynski, asked people to pray for the pope.

When the Mass ended, the crowd spontaneously broke into Poland's official anthem the Dabrowski mazurka with the words ... "Poland has not yet perished." I sang with everyone else. (p. 95)

The Mass finished and Sonya returned to her apartment to be told that the Miami Herald newspaper had called. They wanted to know if Sonya had news on the local reaction to the pope's shooting. She dictated on the phone what she had seen and heard:

- Wails of grief

- Huge size of crowd

- Hopefulness about the pope

- Gratitude he had not been killed

The following day the news reported that the pope was making a good recovery.

Later that month Poland was shocked again: this time by the death of Cardinal Stefan Wyszynski.

- Born 1901

- Primate of Poland

- Named as a cardinal on 29 November 1952

- House arrest from 1953-56 at end of Stalinist period

- Died in Warsaw on 28 May 1981 aged 79.

- Open-air funeral in Warsaw's Victory Sqaure attended by 300,000 mourners

- Solidarity leader Lech Walesa and union delegation provided honour guard at coffin

Sonya witnessed the funeral service for Cardinal Stefan Wyszynski from a window of the Victoria hotel. She then went to the UPI office and filed her story for the Miami Herald newspaper.

Shortages Get Worse

By the end of July the shortages in Poland had got worse:

- Meat allowance cut by 20%

- Eggs had disappeared as there was no feed for chickens

- Cigarettes about to be rationed

- Price hikes and wage freezes

In early August Sonya went into the center of the city and came across a huge traffic jam:

100 buses and ... trucks all decorated with red-and-white Polish flags and Solidarity placards with their lights flashing and their horns blazing as they jammed Warsaw's main intersection at Marszalkowska and Jerozolimskie Avenues. (p. 171)

Solidarity had called a transport strike to protest at the growing food shortages. The buses and trucks were surrounded by police and police vehicles.

"We can't eat ration coupons," banners proclaimed. (p. 173)

On the third day of the action factory and transport workers in Warsaw went on strike for a few hours. The situation in the country was tense. The worst since the warning strike in March. Solidarity declared the action a success and said that talks would continue with the Polish government. The government in contrast decided to break off further talks. A few days later the Polish government leaders met with the Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev (USSR) in Crimea to discuss the crisis in Poland.

It wasn't just the Poles who were struggling from the shortage of supplies: their animals were also suffering. The dog pound in Warsaw had to euthanize 150 dogs a month. The Director of Warsaw zoo was worried that they were finding it hard to get the right seeds for their rare birds and didn't know if they would be able to find enough coal to keep the giraffes warm.

Departure

Sonya faced a dilemma: should she stay in Poland or go back to the USA? The increasing tensions in Poland made her feel that she was ready to return home.

Winter was coming soon, and there were holes in my boots, no glue in the whole country to fix them, no new ones to buy in stores. My money was diminishing daily ... Could I get another [student] visa extension? (p. 215)

On 18 October Polish Communist Party leader Stanislaw Kania was replaced as head of the Polish Communist Party by Prime Minister General Jaruzelski who was also Defence Minister. The Polish Communist Party demanded a ban on all strikes: Solidarity refused. Poland stood on the brink.

Sonya's visa extension ran out in early November and she left the country by train on the Chopin Express to Vienna.

On 13 December 1981 the Polish government, headed by General Jaruzelski, imposed martial law in Poland. Tanks appeared on the streets of Warsaw. The leaders of Solidarity were arrested and jailed.

Related Material

- AP publishes memoir on Poland’s fight for freedom during Solidarity (24 February 2023)